The rise and fall of 3Dfx

The Christmas holidays usually mean taking a break from the usual everyday routine and focus more on the important relationships in our lives, like family and close friends. To me, this also somehow includes having the time to think about things technology-wise that either are new or haven’t crossed my mind in a long time.

During this past Christmas season, I strangely found myself thinking about a Christmas of the past, more precisely December of 1997. Why is this interesting? Because that was the year when I bought my first 3D Accelerator graphics card.

A little bit of history

Videogames have not always looked like they do today. Certainly they didn’t go straight from Pac-Man to Fallout 3 either.

There was a time in the early 90’s when game developers discovered that they

could represent entire worlds using computer graphics and three-dimensional

shapes. They  also discovered that it was possible to cover those shapes with images instead of just applying some colors, to make them look more realistic. There was also a growing interest in reproducing physical aspects of the real world in 3D graphics, like the effects of lights and shadows, water, fog, reflexes etc.

also discovered that it was possible to cover those shapes with images instead of just applying some colors, to make them look more realistic. There was also a growing interest in reproducing physical aspects of the real world in 3D graphics, like the effects of lights and shadows, water, fog, reflexes etc.

Unluckily, the processing power of the CPUs available in the market at that time wasn’t quite up to the challenge. In spite of the advanced algorithms that were developed to render 3D graphics in software, the end results were always far from what we would call “realistic”.

The rise

Up until 1996, when a company called 3Dfx Interactive based in San Jose,

California, published the first piece of computer hardware exclusively dedicated

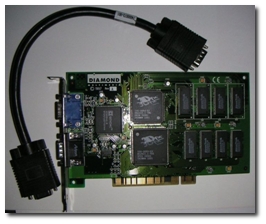

to rendering 3D graphics on a PC screen: a 3D Accelerator. Their product was

called Voodoo Graphics,  and consisted of a PCI card equipped with a 3D graphics processing unit (today known as GPU) running at 50 MHz and 4 MB of DRAM memory.

and consisted of a PCI card equipped with a 3D graphics processing unit (today known as GPU) running at 50 MHz and 4 MB of DRAM memory.

The company also provided a dedicated API called Glide, that developers could use to interact with the card and exploit its capabilities. Glide was originally created as a subset of the industry-standard 3D graphics library OpenGL, specifically focused on the functionality required for game development. Another key difference between Glide and other 3D graphics APIs was that the functions exposed in Glide were implemented directly with native processor instructions for the GPU on the Voodoo Graphics. In other words, while OpenGL, and later on Microsoft’s Direct3D, provided an abstraction layer that exposed a common set of APIs independent of the specific graphics hardware that would actually process the instructions, Glide exposed only the functionality supported by the GPU.

This approach gave all 3Dfx cards superior performance in graphics processing, a key advantage that lasted many years, even when competing cards entered the market, such as the Matrox G200, ATI Rage Pro and Nvidia RIVA 128. However, this also resulted in some heavy limitations in the image quality, like the maximum resolution of 640×480 (later increased to 800×600 with the second-generation cards called Voodoo 2) and the support for 16-bit color images.

The 3Dfx Voodoo Graphics was designed from the ground up with the sole purpose of running 3D graphics algorithms as fast as possible. Although  this may sound as a noble purpose, it meant that in practice the card was missing a regular VGA controller onboard. This resulted in the need of having a separate video adapter just to render 2D graphics. The two cards had to be connected with a bridge cable (shown in the picture) going from the VGA card to the Voodoo, while another one connected the latter to the screen. The 3D Accelerator would usually pass-through the video signal from the VGA card on to the screen, and engaged only when an application using Glide was running on the PC.

this may sound as a noble purpose, it meant that in practice the card was missing a regular VGA controller onboard. This resulted in the need of having a separate video adapter just to render 2D graphics. The two cards had to be connected with a bridge cable (shown in the picture) going from the VGA card to the Voodoo, while another one connected the latter to the screen. The 3D Accelerator would usually pass-through the video signal from the VGA card on to the screen, and engaged only when an application using Glide was running on the PC.

Being the first on the consumer market with dedicated 3D graphics hardware, 3Dfx completely revolutionized the computer gaming space on the PC, setting a new standard for how 3D games could and should look like. All new games developed from the mid 90’s up to the year 2000 were optimized for running on Glide, allowing the lucky possessors of a 3Dfx (like me) to enjoy great and fluid 3D graphics.

To give you an idea of how 3Dfx impacted games, here is a screenshot of how a popular first-person shooter game like Quake II looked like when running in Glide-mode compared to traditional software-based rendering.

The fall

If the 3Dfx was so great, why isn’t it still around today, you might ask. I asked myself the same question.

After following up the original Voodoo Graphics card with some great successors like the Voodoo2 (1998), Voodoo Banshee, (1998) and Voodoo3 (1999), 3Dfx got overshadowed by two powerful competitors Nvidia’s GeForce and ATI’s Radeon. A series of bad strategic decisions that lead to delayed and overpriced products, caused 3Dx to lose market share, ultimately reaching bankruptcy in late 2000. Apparently 3Dfx, by refusing to incorporate 2D/3D graphics chips and supporting Microsoft’s DirectX, became no longer capable of producing cards that lived up to what was the new market’s standard. In 2004 3Dfx opted to be bought by Nvidia, who acquired much of the company’s intellectual property, employees, resources and brands.

Even if 3Dfx no longer exist as a company, it effectively placed a landmark in the history of computer games and 3D graphics, opening the way to games we see today on the stores’ shelves. And the memory of its glorious days still warm the hearts of its fans, especially during cold Christmas evenings.

/Enrico

Enrico Campidoglio

Hi, I'm Enrico Campidoglio. I'm a freelance programmer, trainer and mentor focusing on helping teams develop software better. I write this blog because I love sharing stories about the things I know. You can read more about me here, if you like.