BDD all the way down

TDD makes sense and improves the quality of your code. I don’t think anybody could argue against this simple fact. Is TDD flawless? Well, that’s a whole different discussion.

But let’s back up for a moment.

Picture this: you’ve just joined a team tasked with developing some kind of software which you know nothing about. The only thing you know is that it’s an implementation of Conway’s Game of Life as a web API. Your first assignment is to develop a feature in the system:

In order to display the current state of the Universe

As a Game of Life client

I want to get the next generation from underpopulated cells

You want to implement this feature by following the principles of TDD, so you know that the first thing you should do is start writing a failing test. But, what should you test? How would you express this requirement in code? What’s even a cell?

If you’re looking at TDD for some guidance, well, I’m sorry to tell you that you’ll find none. TDD has one rule. Do you remember what the first rule of TDD is? (No, it’s not you don’t talk about TDD):

Thou shalt not write a single line of production code without a failing test.

And that’s basically it. TDD doesn’t tell you what to test, how you should name your tests and not even how to understand why they fail in first place.

As a programmer, the only thing you can think of, at this point, is writing a test that checks for nulls. Arguably, that’s the equivalent of trying to start a car by emptying the ashtrays.

Let the behavior be your guide

What if we stopped worrying about writing tests for the sake of, well, writing tests, and instead focused on verifying what the system is supposed to do in a certain situation? That’s called behavior and a lot of good things may come out of letting it be the driving force when developing software. Dan North noticed this during his research, which ultimately led him to the formalization of Behavior-driven Development:

I started using the word “behavior” in place of “test” in my dealings with TDD and found that not only did it seem to fit but also that a whole category of coaching questions magically dissolved. I now had answers to some of those TDD questions. What to call your test is easy – it’s a sentence describing the next behavior in which you are interested. How much to test becomes moot – you can only describe so much behavior in a single sentence. When a test fails, simply work through the process described above – either you introduced a bug, the behavior moved, or the test is no longer relevant.

Focusing on behavior has other advantages, too. It forces you to understand the context in which the feature you’re developing is going work. It makes you see the value that it brings for the users. And, last but not least, it forces you to ask questions about the concepts mentioned in the requirements.

So, what’s the first thing you should do? Well, let’s start by understanding what a generation of cells is and then we can move on to the concept of underpopulation:

Any live cell with fewer than two live neighbors dies, as if by needs caused by underpopulation.

Acceptance tests

At this point we’re ready to write our first test. But, since there’s still no code for the feature, what exactly are we supposed to test? The answer to that question is simpler than you might expect: the system itself.

We’re implementing a requirement for our Game of Life web API. The user is supposed to make an HTTP request to a certain URL sending a list of cells formatted as JSON and get back a response containing the same list of cells after the rule of underpopulation has been applied. We’ll know we’ll have fulfilled the requirement when the system does exactly that. It’s, in other words, the requirement’s acceptance criteria. It sure sounds like a good place to start writing a test.

Let’s express it the way formalized by Dan North:

Scenario: Death by underpopulation

Given a live cell has fewer than 2 live neighbors

When I ask for the next generation of cells

Then I should get back a new generation

And it should have the same number of cells

And the cell should be dead

Here, we call the acceptance criteria scenario and use a Given-When-Then syntax to express its premises, action and expected outcome. Having a common language like this for expressing software requirements is one of the greatest innovations brought by BDD.

So, we said we were going to test the system itself. In practice, that means we must put ourselves in the user’s shoes and let the test interact with the system at its outmost boundaries. In case of a web API, that translates in sending and receiving HTTP requests.

In order to turn our scenario into an executable test, we need some kind of framework that can map the Given-When-Then sentences to methods. In the realm of .NET, that framework is called SpecFlow. Here’s how we could use it together with C# to implement our test:

IEnumerable<dynamic> generation;

HttpResponseMessage response;

IEnumerable<dynamic> nextGeneration;

[Given]

public void Given_a_live_cell_has_fewer_than_COUNT_live_neighbors(int count)

{

generation = new[]

{

new { Alive = true, Neighbors = --count }

};

}

[When]

public void When_I_ask_for_the_next_generation_of_cells()

{

response = WebClient.PostAsJson("api/generation", generation);

}

[Then]

public void Then_I_should_get_back_a_new_generation()

{

response.ShouldBeSuccessful();

nextGeneration = ParseGenerationFromResponse();

nextGeneration.ShouldNot(Be.Null);

}

[Then]

public void Then_it_should_have_the_same_number_of_cells()

{

nextGeneration.Should(Have.Count.EqualTo(1));

}

[Then]

public void Then_the_cell_should_be_dead()

{

var isAlive = (bool)nextGeneration.Single().Alive;

isAlive.ShouldBeFalse();

}

IEnumerable<dynamic> ParseGenerationFromResponse()

{

return response.ReadContentAs<IEnumerable<dynamic>>();

}

As you can see, each portion of the scenario is mapped directly to a method by matching the words used within the sentences separated by underscores.

At this point, we can finally run our acceptance test and watch it fail:

Given a live cell has fewer than 2 live neighbors

-> done.

When I ask for the next generation of cells

-> done.

Then I should get back a new generation

-> error: Expected: in range (200 OK, 299)

But was: 404 NotFound

As expected, the test fails on the first assertion with an HTTP 404 response. We know this is correct since there’s nothing listening to that URL on the other end. Now that we understand why this test fails, we can now officially start implementing that feature.

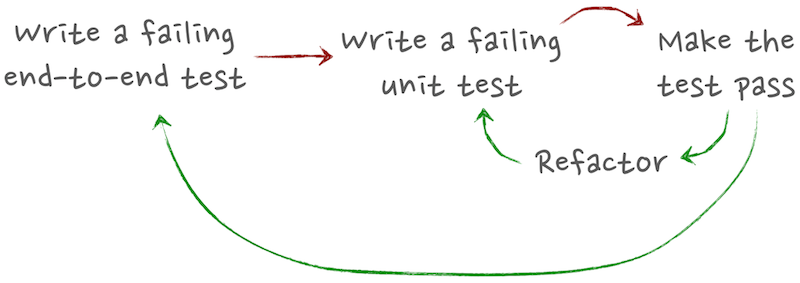

The TDD cycle

We’re about to get our hands dirty (albeit keeping the code clean) and dive into the system. At this point we follow the normal rules of Test-driven development with its Red-Green-Refactor cycle. However, we’re faced with the exact same problem we had at the boundaries of the system. What should be our first test? Even in this case, we’ll let the behavior be our guiding light.

If you have experience writing unit tests, my guess is that you’re used to write one test class for every production code class. For example, given SomeClass you’d write your tests in SomeClassTests. This is fine, but I’m here to tell you that there’s a better way. If we focus on how a class should behave in a given situation, wouldn’t it be more natural to have one test class per scenario?

Consider this:

public class When_getting_the_next_generation_with_underpopulation

: ForSubject<GenerationController>

{

}

This class will contain all the tests related to how the GenerationController class behaves when asked to get the next generation of cells given that one of them is underpopulated.

But, wait a minute. Wouldn’t that create a lot of tiny test classes?

Yes. One per scenario to be precise. That way, you’ll know exactly which class to look at when you’re working with a certain feature. Besides, having many small cohesive classes is better than having giant ones with all kinds of tests in them, don’t you think?

Let’s get back to our test. Since we’re testing one single scenario, we can structure it much in same way as we would define an acceptance test:

For each scenario there's exactly one context to set up, one action and one or more assertions on the outcome.

As always, readability is king, so we’d like to express our test in a way that gets us as close as possible to human language. In other words, our tests should read like specifications:

public class When_getting_the_next_generation_with_underpopulation

: ForSubject<GenerationController>

{

static Cell solitaryCell;

static IEnumerable<Cell> currentGen;

static IEnumerable<Cell> nextGen;

Establish context = () =>

{

solitaryCell = new Cell { Alive = true, Neighbors = 1 };

currentGen = AFewCellsIncluding(solitaryCell);

};

Because of = () =>

nextGen = Subject.GetNextGeneration(currentGen);

It should_return_the_next_generation_of_cells = () =>

nextGen.ShouldNotBeEmpty();

It should_include_the_solitary_cell_in_the_next_generation = () =>

nextGen.ShouldContain(solitaryCell);

It should_only_include_the_original_cells_in_the_next_generation = () =>

nextGen.ShouldContainOnly(currentGen);

It should_mark_the_solitary_cell_as_dead = () =>

solitaryCell.Alive.ShouldBeFalse();

}

In this case I’m using a test framework for .NET called Machine.Specifications or MSpec. MSpec belongs to a category of frameworks called BDD-style testing frameworks. There are at least a few of them for almost every language known to men (including Haskell). What they all have in common is a strong focus on allowing you to express your tests in a way that resembles requirements.

Speaking of readability, see all those underscores, static variables and lambdas? Those are just the tricks MSpec has to pull on the C# compiler, in order to give us a domain-specific language to express requirements while still producing runnable code. Other frameworks have different techniques to get as close as possible to human language without angering the compiler. Which one you choose is largely a matter of preference.

Wrapping it up

I’ll leave the implementation of the GenerationController class as an exercise for the Reader, since it’s outside the scope of this article. If you like, you can find mine over at GitHub.

What’s important here, is that after a few rounds of Red-Green-Refactor we’ll finally be able to run our initial acceptance test and see it pass. At that point, we’ll know with certainty that we’ll have successfully implemented our feature.

Let’s recap our entire process with a picture:

This approach to developing software is called Outside-in development and is described beautifully in Steve Freeman’s & Nat Pryce’s excellent book Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests.

In our little exercise, we grew a feature in our Game of Life web API from the outside-in, following the principles of Behavior-driven Development.

Presentation

You can see a complete recording of the talk I gave at Foo Café last year about this topic. The presentation pretty much covers the material described in this articles and expands a bit on the programming aspect of BDD. I hope you’ll find it useful. If have any questions, please fill free to contact me directly or write in the comments.

Here’s the abstract:

In this session I’ll show how to apply the Behavior Driven Development (BDD) cycle when developing a feature from top to bottom in a fictitious.NET web application. Building on the concepts of Test-driven Development, I’ll show you how BDD helps you produce tests that read like specifications, by forcing you to focus on what the system is supposed to do, rather than how it’s implemented.

Starting from the acceptance tests seen from the user’s perspective, we’ll work our way through the system implementing the necessary components at each tier, guided by unit tests. In the process, I’ll cover how to write BDD-style tests both in plain English with SpecFlow and in C# with MSpec. In other words, it’ll be BDD all the way down.

Enrico Campidoglio

Hi, I'm Enrico Campidoglio. I'm a freelance programmer, trainer and mentor focusing on helping teams develop software better. I write this blog because I love sharing stories about the things I know. You can read more about me here, if you like.