A gentle introduction to mechanical keyboards

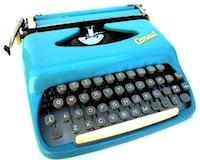

I love typing. I still remember how I, as a kid, used to borrow my mother’s Diplomat typewriter from 1964 and started hammering away on it, pretending to type some long text:

“It sure sounds like you’re a fast typist!”

she would say when she heard the racket coming from my room. Little did she know that what came out on the sheet of paper was actually gibberish. Or maybe she was just being kind.

Anyway, I enjoyed the feeling of pressing those stiff plastic buttons and hear the sound made by the metallic arm every time it punched a letter.

Today, I continue to enjoy a similar experience on my computer by using a mechanical keyboard.

So, what’s a mechanical keyboard?

First and foremost, let’s get the terminology straight by answering that burning question.

Wikipedia’s definition gives us a good starting point, although it’s still pretty vague:

Mechanical-switch keyboards use real switches underneath every key. Depending on the construction of the switch, such keyboards have varying response and travel times.

That leaves us wondering: what do they mean by real switches? Well, in this case real means physical, in the sense that under each key there’s a metal spring that compresses every time you press a key. The spring is housed inside a plastic device that makes sure the key is registered by the computer at a specific point in time while the key is being pressed. That device is called a switch.

So, let’s reformulate the definition of a mechanical keyboard:

A keyboard is considered mechanical if it uses metal springs underneath each key.

It’s still true that there are different types of mechanical switches, each with their own special characteristics. The kind of switch used in a mechanical keyboard determines the overall feeling you’ll get when you type on it.

A little bit of history

At this point you might rightfully wonder:

Wait a minute. Aren’t all keyboards mechanical?

No, they are not. At least not anymore. The keyboards sold with the first personal computers back in the late 70’s, however, were indeed.

Back then, computer keyboards were designed to mimic the feeling and behavior of typewriters. These were robust pieces of hardware, built with quality in mind. They used solid materials, like metal plates and thick ABS plastic frames. The keys were stiff enough to allow the typist to rest her fingers on the home row without accidentally pressing any key.

If you’re in your 30’s, chances are you remember how it felt to type on one of these keyboards, maybe in front of a Macintosh or a Commodore 64. All throughout the 80’s and early 90’s, every keyboard was mechanical. And heavy.

But then things started to change. When PCs became a mass market product, the additional cost of producing quality mechanical keyboards to go along with them was no longer justifiable. Consumers didn’t seem to care, either. As graphical user interfaces (GUI) grew in popularity during the mid 80’s, the keyboard, which had been the primary way to interact with computers up to that point, had to leave room to another kind of input device: the mouse.

Keyboards, like computers, became a commodity sold in large volumes. In an effort to continuously try to bring the production costs down, new designs and materials became mainstream. Focus shifted from quality and durability to cost effectiveness.

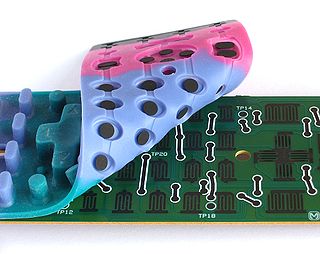

Consequently, the heavy metal plates disappeared in favor of cheaper silicon membranes put on top of electrical matrixes. Metal springs left room to air pads under each key. This keyboard technique is called rubber dome or membrane, and is to this day the most common type of keyboard sold with desktop computers.

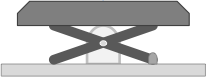

For laptops, a new kind of low profile rubber dome switch began to appear. They were made out of thin plastic parts and were called scissors because of their collapsable X shape.

While today’s mainstream keyboards certainly serve their purpose, they have a limited lifetime.

With time and usage, the rubber bubbles eventually wear out, which means you have to press harder on the keys to activate them. The letters printed on the keys fade or peel off. The cheap plastic parts loosen up or bend. And by the time you’re finally ready to throw those suckers in the bin, they’ve managed to drive you nuts.

Mechanical keyboards, on the other hand, are built to last.

As a testimony of their extreme durability, I can tell you that the oldest one in my collection is an Apple Extended Keyboard II dated all the way back to 1989 and it still works like a charm.

That’s a 25 years old piece of hardware still in perfectly good condition. So much, in fact, that I use it daily as my primary keyboard at home.

It’s all about the feeling

However, believe it or not, the biggest problem with rubber dome keyboards isn’t their fragility. It’s the fact that they’re an ergonomic nightmare.

We said that the switches are responsible for telling the computer which key is being pressed. The precise moment when that happens is called actuation point. The distance between a key’s rest position and when it’s fully pressed down is called key travel.

Now, in rubber dome keyboards, the only way to actuate a key is to press it all the way to the bottom (also known as bottoming out). That’s when the silicon air bubble beneath it gets squashed, thus sending an electrical signal to the computer. This means that your fingers have to travel a longer distance when typing, which puts a strain on your hands and wrists.

Mechanical keys, on the other hand, are actuated before they bottom out. For most types of switches, that happens about half way through the key travel.

What does this mean in practice? Well, it means that you don’t have to press as hard on your keyboard when you type. Your fingers don’t have to travel as much and, consequently, you don’t get as fatigued. It may even help you type faster.

To each his own switch

There are at least a dozen different kinds of mechanical switches available on the market today. That number doubles if you count the vintage ones.

Each and every one of them has its own way to physically actuate a key, which conforms its own distinctive feel.

The buckling spring switch patented by IBM in 1971, for example, actuates a key by having the internal spring buckle outwards as it collapses. That activates a plastic hammer located beneath the spring, which, upon hitting a contact, closes an electrical circuit. As the spring buckles, it hits the inner wall of its plastic housing producing a loud “click” sound. That feedback signals the typist that the key has been registered.

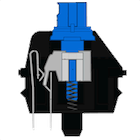

The modern Cherry MX Blue switch, on the other hand, uses a leaf spring pushed by a plastic slider (the grey one in the picture) as it passes by on its way down. When the slider is half way through, the leaf spring encounters no more resistance from the slider, thus closing a circuit that signals the computer about the key press. As the grey slider hits the bottom of the switch, it emits a high pitched “click” sound similar to the one of a mouse button.

Don’t worry, I won’t get into all the nuts and bolts of all the different switches. The Internet will happily provide you more information than you can possibly ask for in that regard.

The important thing to remember is that the ergonomic properties of a mechanical keyboard are determined by three fundamental characteristics of its switches:

- Tactility

- Force

- Sound

Let’s look at each of them briefly.

Tactility

A switch is called tactile if it gives some kind of feedback about when a key is actuated. This is usually done by significantly dropping the key’s resistance the instant it gets registered. Some switches even accompany that with a “click” sound and are therefore referred to as “clicky”.

Force

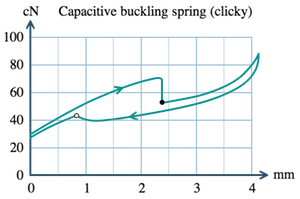

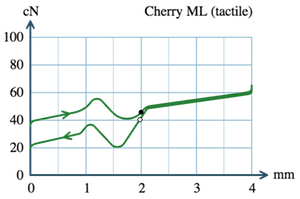

The force indicates how hard you have to press down a key in order to actuate it. This is measured in centinewtons (cN) or, more commonly grams-force (gf). In practice they’re interchangeable, since 1 cN is roughly equivalent to 1 gf (more precisely 1 cn = 1.02 gf).

Switches get progressively stiffer the further down you press a key, which, again, helps you avoid bottoming out. A soft switch requires about 45 cN to actuate. A stiff one is about twice that, around 80 cN.

These are called force graphs and indicate how much force in cN (Y axis) is required to press a key during its travel in mm (X axis) from rest position to bottom. Did you notice the sudden drop in force about half way through the travel? That’s how tactile switches announce that the key has been actuated, as shown by the little black dot.

Sound

As I mentioned earlier, certain switches emit a “click” sound when they get actuated. This extra piece of feedback can either be pleasurable (even nostalgic if you will) or totally annoying. I strongly advise you to investigate how the people who will be sitting next to you feel about clicky keyboards before buying one. And telling them that all keyboards sounded like that back in the 80’s no longer cuts it.

Wrapping it up

I know it sounds crazy, but I barely scratched the surface of what there is to know about mechanical keyboards. However, the purpose of this post was to give you an idea about what they are and where they come from, and I hope I’ve succeeded in that.

If you’re eager to know more, fear not. I intend to write more about this topic. Next time, I’ll start reviewing some of my favorite mechanical keyboards. In the meantime, take a look at the official guide to mechanical keyboards put together by this growing community of keyboard enthusiasts.

Enrico Campidoglio

Hi, I'm Enrico Campidoglio. I'm a freelance programmer, trainer and mentor focusing on helping teams develop software better. I write this blog because I love sharing stories about the things I know. You can read more about me here, if you like.