The importance of a good-looking history

“Study the past if you would define the future.” ~Confucius

Since the dawn of civilization, common sense has taught us that the way forward starts by knowing how we got here in the first place. While this powerful principle applies to practically all aspects of life, it’s especially true when developing software.

For us programmers, the rear mirror through which we look at the history of a code base before we go on to shape its future is version control. Among all the information captured by a version control tool, the most critical ones are the commit messages.

Git’s view of history

When we’re trying to understand how a piece of software has evolved over time, the first thing we tend to do is look at the trails of messages left by the programmers who came before us. Those sentences hold the key to understanding the choices that molded the software into what it is today.

In other words, what you write in these messages is crucial and you should put extra effort in making them as loud and clear as possible.

This is true regardless of what version control system you happen to be using. However, it is especially true for Git. Why? Because Git simply holds the history of your code to a higher standard.

As Linus Torvalds explained in his excellent Teck Talk at Google back in 2007, Git evolved out of the need to manage the development of the Linux kernel, a humongous open source project with a 20 year history and hundreds of contributors from all around the world.

If source code history has ever played a more critical role in a software project, the Linux kernel is where it’s at.

Torvalds’ attention to history is also reflected in the features he built into his own distributed version control tool. To put it in his own words:

I want clean history, but that really means (a) clean and (b) history.

Regarding the “clean” part, he goes on to elaborate:

Keep your own history readable.

Some people do this by just working things out in their head first, and not making mistakes. But that’s very rare, and for the rest of us, we use “git rebase” etc. while we work on our problems.

Don’t expose your crap.

When it comes to “history”, he says:

People can (and probably should) rebase their private trees (their own work). That’s a cleanup. But never other people’s code. That’s a “destroy history”

You see, Git grants you all the tools you need to go back in time and rewrite your own commits (for example by changing their order, contents and messages) because having a clear history of the code matters. It matters to the sanity of whoever is working on it; present or future.

A legacy of e-mails

Having talked about the importance of keeping your history clean, let’s take the concept one step further.

When you use Git, you should not only pay attention to the contents of your commit messages, but also how they're formatted.

There’s a reason for that. As Torvalds himself stated in his Google talk, for a long period of time the history of the Linux kernel was captured in e-mail threads with patches attached:

“For the first 10 years of kernel maintenance we literally used tarballs and patches.” ~Linus Torvalds

Even in the early days of Git, e-mail was still used as a way to send patches among collaborators of the Linux project.

If you look closely, you’ll notice that the concept of e-mail is pretty pervasive throughout Git. Here’s some evidence off the top of my head:

- Every user has to have an e-mail address which is always part of the commit’s metadata

- The

git format-patchandgit amcommands are specifically designed to convert commits into e-mails with patches as attachments - Both

git blameandgit shortloghave special options to display the committers’ e-mail addresses instead of their names - The

git logcommand has dedicated placeholders to indicate a commit message’s subject and body

The last one is particularly interesting. Git seems to assume that a commit message is divided in two parts:

- A short one-sentence summary

- An optional longer description defined in its own paragraph separated by an empty line

A “well-formed” Git commit message would then look like this:

A short summary, possibly under 50 characters.

A longer description of the change and the reasoning

behind it for the future generations to know.

Even better if it's wrapped at 80 characters so that

it will look good in the console.

If you follow this simple convention, Git will reward you by going out of its way to show you your history in the prettiest way possible. And that’s a good thing.

Formatting matters

Once you fall into the habit of keeping your commit messages under 50 characters and relegate any longer description to a separate paragraph, you can start pretty-printing your history in almost any way you like.

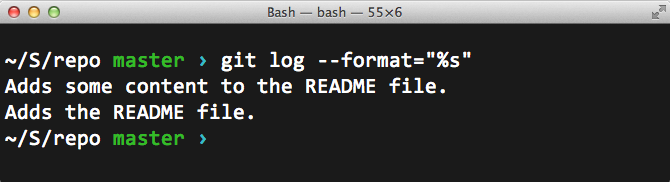

For example, you could choose to only display the commits’ summaries by using the %s placeholder in the --format option of git log:

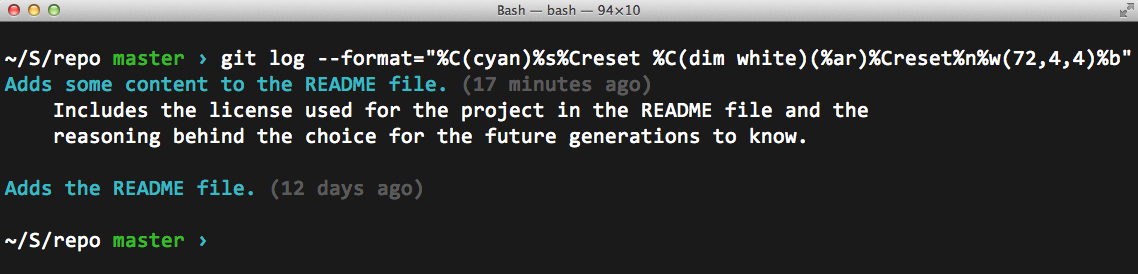

Or you could go crazy with all kinds of colors and indentation:

The format string I used in this particular example can be broken down as:

"%C(cyan)%s%Creset %C(dim white)(%ar)%Creset%n%w(72,4,4)%b"

where:

%C(cyan)colors the following text in cyan%sshows the commit summary%Cresetrestores the default color for the text%C(dim white)colors the following text in grey%arshows the time of the commit relative to now%nadds a newline character%w(72,4,4)wraps the following text at 72 characters. Then, indents the first line as well as the remaining ones with 4 spaces%bshows the long description of the commit, if any

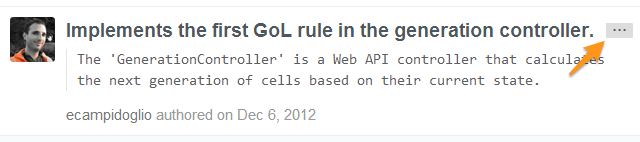

GitHub itself follows this convention when showing the commit history of a project. In fact, they will only show you the summary of each commit by default. If there’s a longer description available, they allow you to expand it with the press of a button.

Pretty-printed commit message on GitHub

Pretty-printed commit message on GitHub

Enforcing the rule

Of course, this all works best if everyone on the project agrees to follow the convention.

But how do you ensure that the team sticks to the golden rule of pretty commits™?

Well, you give your peers a gentle nudge at exactly the right moment: just when they’re about to make a commit. This is what Jeff Atwood calls the “Just In Time” theory:

You do it by showing them:

- the minimum helpful reminder

- at exactly the right time

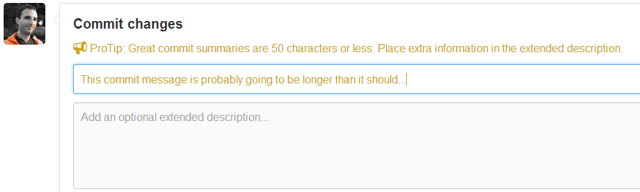

GitHub does this already, both on the Web:

Commit message being validated in the GitHub web UI

Commit message being validated in the GitHub web UI

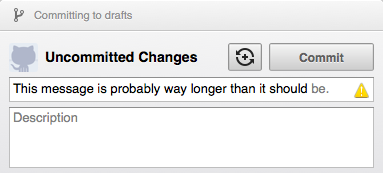

and in its desktop clients:

Commit message being validated in GitHub for Mac...

Commit message being validated in GitHub for Mac...

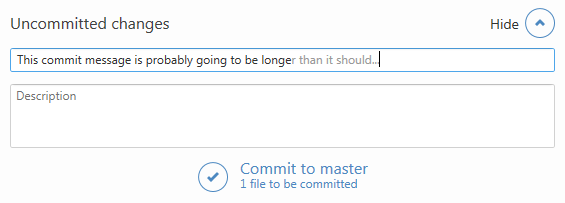

...and in GitHub for Windows

...and in GitHub for Windows

But what if you prefer to use Git from the command line, the way it should be?

Easy. You write a shell script that gets triggered by Git’s client side hooks every time you’re about to do a commit. In that script, you make sure the message is formatted according to the rules.

Here’s my version of it:

#!/bin/sh

#

# A hook script that checks the length of the commit message.

#

# Called by "git commit" with one argument, the name of the file

# that has the commit message. The hook should exit with non-zero

# status after issuing an appropriate message if it wants to stop the

# commit. The hook is allowed to edit the commit message file.

DEFAULT="\033[0m"

YELLOW="\033[1;33m"

function printWarning {

message=$1

printf >&2 "${YELLOW}$message${DEFAULT}\n"

}

function printNewline {

printf "\n"

}

function captureUserInput {

# Assigns stdin to the keyboard

exec < /dev/tty

}

function confirm {

question=$1

read -p "$question [y/n]"$'\n' -n 1 -r

}

messageFilePath=$1

message=$(cat $messageFilePath)

firstLine=$(printf "$message" | sed -n 1p)

firstLineLength=$(printf ${#firstLine})

test $firstLineLength -lt 51 || {

printWarning "Tip: the first line of the commit message shouldn't be longer than 50 characters and yours was $firstLineLength."

captureUserInput

confirm "Do you want to modify the message in your editor or just commit it?"

if [[ $REPLY =~ ^[Yy]$ ]]; then

$EDITOR $messageFilePath

fi

printNewline

exit 0

}

In order to use it in your local repo, you’ll have to manually copy the script file into the .git\hooks directory and call it commit-msg. Finally, you’ll have grant execute rights to the file in order to make it runnable:

cp commit-msg somerepo/.git/hooks

chmod +x somerepo/.git/hooks/commit-msg

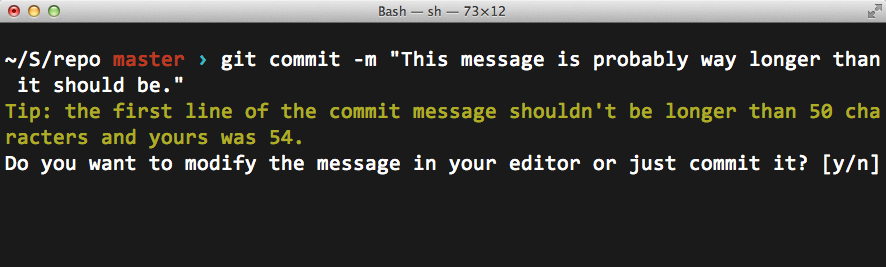

From that point forward, every time you attempt to create a commit that doesn’t follow the rules you’ll get a chance to do the right thing:

If you choose to press y, the commit message will open up in your default text editor from which you can rewrite it properly. Pressing n, on the other hand, will override the rule altogether and commit the message as it is.

Not that you’d ever want to do that.

If you're interested in learning other techniques like the one described in this article, you should check out my Pluralsight course Git Tips and Tricks.

Enrico Campidoglio

Hi, I'm Enrico Campidoglio. I'm a freelance programmer, trainer and mentor focusing on helping teams develop software better. I write this blog because I love sharing stories about the things I know. You can read more about me here, if you like.