The Invisible Commits (Part 1)

Your repository has more commits than what meets the eye. They hide somewhere in the .git directory—where you can’t see them—but they’re there. I call them the invisible commits. Knowing where to find them can mean the difference between recovering your work and losing it to the sands of time.

One of the things you’ll often hear enthusiasts like me say is “with Git, you can’t lose your work”. If you wanted to challenge me on that statement, you’d be right—after all, there are no absolutes in computer science.

That’s why I always follow up with an asterisk:

…as long as you’ve committed it.1

If that sounds vague to you, don’t worry—explaining what I mean by that is the very topic of this article.

Resilience by Design

The fact that Git is resilient is no coincidence—it was a deliberate design choice made by Linus Torvalds. Here’s what he wrote in response to a question about data corruption back in 2007:

That was one of the design goals for git (i.e. the “you know you can trust the data” thing relies on very strong protection at all levels, even in the presence of disk/memory/cpu corruption).

“At all levels”—he said—implying that Git has built-in safeguards not only against hardware failure, but also human error.

That’s why experienced Git users will often tell you to calm down in the face of what seems like a disaster. They’re right—in the vast majority of cases you can, in fact, recover commits that you thought were lost. The key—as with many things in Git—is to know where to find them.

Solid advice in tough situations.

Solid advice in tough situations.

In this article series, I’ll talk about what I like to call the invisible commits; commits that you don’t see, but are there as an insurance policy, just in case you ever need to have them back.

Let’s start with the easy one: the reflog.

The Reflog

I’ve talked about the mighty reflog in more than one occasion. Simply put, the reflog is a journal which records the values of the branch and HEAD references over time. This journal is local to a repository, meaning it can’t be shared by pushing it to remote repositories.

Every time you create a commit, your current branch reference is modified to point to that commit; by the same token, every time you switch to a different branch (for example by using git checkout) the HEAD reference is modified to point to that branch.2

When that happens, the previous and the current value of the reference gets recorded in the reflog belonging to that reference. Go ahead, take a look at a branch’s reflog by saying:

git reflog <branchname>

Or for HEAD:

git reflog

What you get back is something like this:

20da2b6 HEAD@{0}: commit (amend): WIP: reinventing the wheel

176ec0a HEAD@{1}: rebase finished: returning to refs/heads/develop

176ec0a HEAD@{2}: rebase: WIP: reinventing the wheel

2b60b60 HEAD@{3}: rebase: checkout master

2b60b60 HEAD@{4}: cherry-pick: Reticulates the splines

e7db79d HEAD@{5}: checkout: moving from develop to master

93ced10 HEAD@{6}: commit: Does some refactoring

It’s a list where each entry contains a few pieces of information:

- The SHA-1 hash of the commit referenced by the entry.

- The name of the entry itself in the form

reference@{position}. - The name of the operation that caused the reference to change, for example a

commit,checkoutorrebase. - A description associated to the entry; this could be the commit message if it was commit operation or the source and destination branch in case of a checkout.

The reason why this is important in the context of data recovery, is that you can reference reflog entries as you would regular commits.

Recovering Commits from the Reflog

That’s enough theory. Let’s talk about this works in practice. Imagine you have history that looks like this:

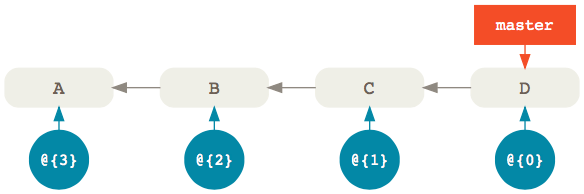

There’s a master branch with four commits. Now, assuming you haven’t modified history in any way, the reflog that belongs to the master branch (shown in blue) is also going to have four entries—one for each commit—with @{0} being the most recent.

Now, let’s imagine that, in the heat of the moment, you accidentally removed the last two commits in your master branch with:

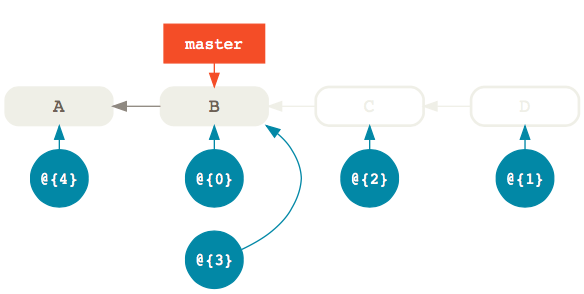

git reset --hard master~2

Now D and E are no longer reachable from master so running git log won’t show them. They’re by all accounts gone, but what if you want to get them back? Where do you find them?

Well, the reflog is still pointing to D and E, you just can’t see it. What used to be entry @{0} became @{1} and a new @{0} entry was created to point to the same commit as master, that is B. Of course, all other entries also shifted by one.

So, if you want to restore the master branch to the same commit it referenced before you modified it, you can simply reset it to the previous reflog entry @{1} which still points to commit D:

git reset --hard @{1}

The important thing to remember is this:

The

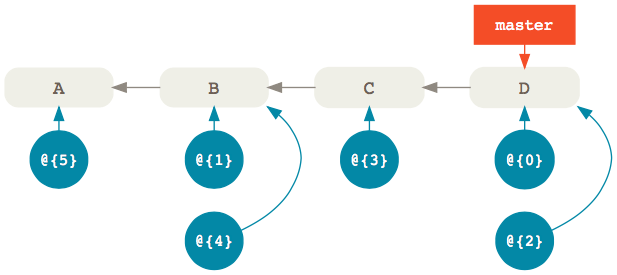

@{0}entry in the reflog always points to the same commit as the branch itself. Previous entries follow with increments by one like@{1},@{2},@{3}and so on; in other words, the higher the index, the older the entry.

Of course, you can also use the reflog to recover commits that happened way earlier.

For example, let’s say that you want to restore an older commit after you have added a whole bunch of new commits on top of master. Of course, you can’t use git reset because that would remove the new commits.

What you do in that case is apply the older commit on top of master with git cherry-pick:

git cherry-pick @{90}

And voilà—the commit referenced by the reflog entry with index 90 is back in your master branch.3

Searching the Reflog

The last example implies that you can find the commit you’re looking for by simply scrolling through the reflog. Of course, that’s not always the case.

So, what do you do when you want to recover an invisible commit from the reflog, but you don’t know where it is?

The answer is, you search for it using git log. Here’s an example:

git log --grep="Some commit message" --walk-reflogs --oneline

Let’s unpack this command:

--grepallows you to find commits whose message matches a pattern (which can be a regular expression).--walk-reflogstells thelogcommand to search through the commits referenced by the reflog instead of the ones referenced by a particular branch.--onelineprints out the commit SHA-1, the reflog reference and the commit message in a single line for a more compact output (if you like it, of course).

That’s the kind of search I usually do, but it’s certainly not the only one.

For example, you can also look for commits that happened within a specific time range:

git log --walk-reflogs --since="2 days ago" --before="yesterday" --oneline

Here, we’re specifying the times with the natural formats supported by Linus Torvalds’ amazing approxidate implementation.4

While we’re talking about dates, note that you can also use times instead of indexes when referencing a specific reflog entry. For instance, you can limit your search to just the entries from a particular point in time:

git log --walk-reflogs --oneline master@{"2 days ago"}

This will print out the timestamps when the reflog entry were created instead of their index, which sometimes is more helpful:

20da2b6 master@{Mon Oct 16 11:20:58 2017 +0200}: commit (amend): WIP: reinventing the wheel

176ec0a master@{Mon Oct 16 10:37:51 2017 +0200}: rebase finished: returning to refs/heads/develop

176ec0a master@{Mon Oct 16 10:37:14 2017 +0200}: rebase: WIP: reinventing the wheel

2b60b60 master@{Mon Oct 16 10:37:8 2017 +0200}: rebase: checkout master

Things You Won’t Find in the Reflog

By now, it should be clear that the reflog should your first destination when you’re looking for commits to restore. However, be aware that things won’t stay there forever.

Reflog entries have, in fact, expiration dates. By default, they’re set to expire after 90 days, but you can change that to any number of days by setting the gc.reflogExpire option:

git config --global gc.reflogExpire 120

After that, the entries are deleted from the reflog. 😱

Note that this setting is only valid for entries whose commits are still reachable from a branch; this means that entries whose commits are unreachable from a branch or a tag have a different expire date; the default value for that is 30 days.

This makes sense if you think about it; unreachable commits are more likely to be junk left behind by various history modifications, and can therefore be cleaned out more often.

However, if you do want to keep them around longer, just in case, you can do so by setting the gc.reflogExpireUnreachable option:

git config --global gc.reflogExpireUnreachable 60

Just because Git removes an entry from the reflog, it doesn’t mean that the commit itself is also gone. In fact, the commit will still be around until the next garbage collection.

So, when the reflog is no longer an option, we have to find another way to retrieve our invisible commits. We’ll see how in the next article.

-

Followed by a second asterisk that says “and less than a certain amount of time has passed”. More on this later. ↩

-

There are also other situations that would cause the

HEADreference to change, like, for example, a rebase. ↩ -

Of course, you can also reference commits from other branches’ reflogs; if the commit you’re looking for was in

develop, for example, you could just saygit cherry-pick develop@{90}to bring it into your current branch. ↩ -

Which, I discovered, has since been extracted into its own library. ↩

Enrico Campidoglio

Hi, I'm Enrico Campidoglio. I'm a freelance programmer, trainer and mentor focusing on helping teams develop software better. I write this blog because I love sharing stories about the things I know. You can read more about me here, if you like.